A few months back, I was invited by Maddy Costa and the Dramaturg’s Network to speak on a panel about “Diaspora Dramaturgies”. I still don’t really know what that term means (and perhaps it’s intentionally open) but I always trust an invitation from Maddy, so I said yes, and found myself on a panel with the brilliant, funny, clever minds of Saikat Ahamed and Inua Ellams, who also didn’t really know what “Diaspora Dramaturgies” meant. As a sidenote, I don’t think I’ve ever been on a theatre panel with another South Asian person before, so that in itself was beautiful to experience.

Over the last week, having just come out of a tricky process, making Private Lives – not least in approaching an English classic from the only position I could i.e. as a child of the diaspora – I’ve been thinking a lot about what I wrote for that talk. So I thought I’d share it here.

***

July 2025

I’m Tanuja. I’m a director and dramaturg, working mostly in theatre; but I’ve also worked in related forms including screen, narrative video games, audio drama, dance and installation. I currently have a show on at Bristol Old Vic – which I’d love you to see it, if you haven’t already. It’s a new play by Timothy X Atack, called DELAY. A queer, sci-fi, heartbreaker. And as I directed it, it has of course been subject to my dramaturgy, so perhaps it also reflects some of what I’m offering here today.

DELAY is the latest piece in a longstanding writer/director partnership that I have with Tim – who is also someone who, like me, grew up half-way round the world from where they were born (I was born in Sri Lanka and grew up in County Durham; Tim was born in Leicestershire, and grew up in Brazil). And we talk a lot about how our particular mixed cultural heritages have an ongoing foundational influence on our individual artistic curiosity and perspectives. It’s one of the reasons why Tim and I connected and continue to connect as artists. And that’s not just about the nature of the stories we’re drawn to, but also very much about our interest in how stories land in the world, in terms of genre, form, structure, aesthetics, point of view, and so on.

When I ask myself how my global majority heritage influences my practice as a director and dramaturg – it’s hard to separate it from me, so I can only consider it through tracing back. I was only a year old when my parents left Sri Lanka for the UK. My dad was a doctor. He’d qualified in Sri Lanka, then worked in Nigeria for a while, before getting a more specialist position in the UK. My mum was a nurse, but she had very little English when they first came over, so she didn’t get a job until later – and of course, she had me and then my brother, so she had plenty enough work in caring for us in those first few years.

My mum was the first person in her family to have a passport. In fact, she was the first person in her family to leave the area in which she was born. I didn’t know this until after she died, when one of my cousin’s kids – through a mix of their broken English and my imperfect Sinhalese – told me what an inspiration my mum had been to their generation. For taking that leap – that leap of imagination: to believe that half-way round the world, in another country of unimaginable weather, in another culture, where people spoke another language – that there might be another life possible, another world that might embrace us and offer new hopes and alternative dreams.

I’ve been a Star Wars fan all my life. Return of the Jedi was the first film I ever saw at the cinema. When I return to Star Wars – as I do, often – I recognise how much I love it for how it just throws us in, in-media-res, into this universe of multiple cultures, languages, beings, belief systems. And of course also patriarchy, tyranny, capitalism – but then, that’s our world, right? All these multiple, often inconvenient, often contradictory, yet nevertheless simultaneous things. The Star Wars universe is not just the story of the Skywalker dynasty; it’s also the story of the Rebel Alliance.

This is what happens when I think about my heritage. It resists any kind of legible authenticity. My authenticity is authentically cross-cultural.

I had always thought about myself as ‘in-between’ – resisting containment. All through school I was pulled up for refusing to accept that there was only one way to see something – that extended to logic, and science. Reactionary foolishness perhaps. Though it’s turned out to be good practice for standing my ground in the theatre industry.

Then as I grew older, I became more interested in how ‘in-between’ could also be connecting, rather than resisting. And as I’ve found myself more at ease with the many different outsidernesses inside me, I am moving away, I think, from feeling in-between, towards being multitudes. There are as many ways to tell stories as there are ways to feel alive. I am both Star Wars and Bollywood. I am a daughter of both the ghosts of karmic rebirth and the miners’ strike.

When I think about how my heritage informs my practice as a director and dramaturg, I think about being on an artist residency in Sri Lanka in 2018, and standing on the beach at night in Hikkaduwa, wearing shorts, with bare feet in the sand, looking West across the Indian Ocean; and remembering myself as a 6-year-old, standing on the beach at South Shields, in wellies wrapped in a duffel coat, staring East into the wind across the North Sea.

We see the world differently depending on when and where we see it from.

Where in the world.

When in our lives.

I am not one fixed point, with a fixed identity or a fixed perspective.

Brown is not a genre.

Not all Brown people are the same. I can’t believe I’m saying this out loud in a room full of clever people, but honestly, sometimes the way the theatre industry works, it feels like that’s what it thinks – and it’s not just white industry folks that give me that vibe.

It’s as dangerous for minoritised artists to be restricted to stories which centre their protected characteristics, as it is for underrepresented stories to be limited to niche programmes.

We should ALL have permission to bring our different perspectives to ALL stories that feel relevant or resonant to us. And no-one has the right to decide which stories will or will not be relevant to anyone else. That goes for both artists and audiences of course.

It’s not just about what stories we tell, it’s also about how we tell those stories, with whom – which means who gets to tell which stories and where they get to tell them is important.

I’ve always been drawn to theatre as an experiential form. You’re in the room with the story as it unfolds. I’m interested in sensuousness and emotional immersion. I don’t think about theatre as a particularly intellectual or literary or literal form. I get massively annoyed at that very British Theatre thing of privileging the writer and the idea of authorial voice and intent over everything else. In all honesty, I think that only each audience member can truly own the meaning of a work.

And as part of that invitation to an audience I’m very interested in the more abstract, aesthetic, sensory prompts to meaning-making. The script is one part of a multi-faceted expressive instrument that also conducts meaning through sound, light, rhythm, proximity, absence, bodies, comedy, duration, atmosphere and all those other less literal vocabularies.

This instinct was no doubt fine-tuned through my early career as a producer in live art and contemporary dance. I was seeing a lot of international experimental practice and observing these wildly diverse making processes and performance languages. It showed me that I could be moved and exhilarated by stuff that I didn’t necessarily understand. I mean, the world is full of things that I know to be powerful and true, but they are also strange and mysterious – and I think my favourite art is often interested in that.

A friend once told me there was always love and ghosts in my work.

I come from a culture that believes in reincarnation. Whether I believe it or not.

Perhaps that has something to do with it. I’m steeped in those stories.

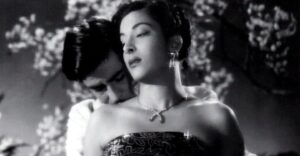

I think most fundamentally, my instinct for non-literary storytelling comes from watching videos of old Hindi movies as a child. I come from a Sri Lankan family – and we’re not Hindi speakers. But that never used to stop my dad obsessively going to the cinema to watch those movies when he was a teenager; and it never stopped me and my brother being captivated by those scratchy black and white films when we were kids. Because of course you can get a sense of what those stories are, and you can catch the drama in the way it’s edited, and you can feel the emotion of those songs – without having any idea what people are actually saying.

I don’t know what diasporic dramaturgy is.

I hope it’s not just another box to contain people who look like me.

I do believe that good dramaturgy should respect the values of each story on its own terms. So, is diasporic dramaturgy any different to just: good dramaturgy?

An approach to dramaturgy that starts not from a singular language of theatre, but from an openness to different and multiple modes of connection and terms of success?

An approach to dramaturgy that understands the play is not everything, that the writer is not the only author of the work?

An approach to dramaturgy that imagines the audience, not as “ticket-buyers” or “communities”, but as extraordinary global individuals, unlocking meaning from the stories we share, through the prism of their own specific histories?

I’ll leave it there. Thank you for listening.