How I’m writing Dark Land Light House:

– In 2008 we outlined a story. A sci-fi horror set on a lighthouse in space. It was meant for radio at first.

– Then we thought about it as a film for a while. We decided it wouldn’t quite work. Or we couldn’t quite afford it. I forget.

– In 2009 I wrote the opening scenes of DLLH as a stage play. I ran away from them. They looked like any other play. I wasn’t convinced it was viable in a theatre.

– Tanuja frowned at me a lot at this point.

– Over the next year Tanuja kept on hitting me with a big stick called the “I’M REALLY INTERESTED IN DARK LAND LIGHT HOUSE AS A PERFORMANCE” stick.

– In 2010 we clarified and rationalised the story, setting rules for our sci-fi universe, until we had something that was as much about atmosphere as plot.

– In 2013 we made a short piece for Mayfest which investigated the type of world we wanted to create for DLLH. Mission statement, nicked from Beckett: “something that works on the audiences’ nerves, as opposed to their intellect.” We told the DLLH story to some nice people at a Kaleider lunchtime talk in Exeter and heard from them how, in theory, it might connect with audiences. Their responses excited us a lot – poetic, thoughtful, visceral.

– In 2013 I attempted to write a first draft of DLLH at a Ferment residency at Halsway Manor. It didn’t work (I was still stuck in a world of hefty dialogue) but I had a great time creating a random arrangement of original and found sounds to work to; it produced the most interesting results we’d had all week, some unexpected and evocative fragments of text. After that, it seemed obvious we needed to build something before writing something.

– I framed it like this: writing DLLH is going to be an orchestration. We have a story, and we want it to be sometimes hard-hitting and scary, sometimes nebulous or yielding, oftentimes lonely, occasionally just plain terrifying, and I know we can do all of that – but I need to know the scale of the ensemble I’m writing for, the kind of instruments we’re going to have in it. I don’t want this to be a show where people admire the cleverness of how we represent space travel / exploding stars / computers / false memories / ghosts. I don’t want it to feel like we solved problems in an inventive way. I want it to feel unified. I want to know what associations and emotions are prompted by the kinds of tech and technique we might use. I want to build our production into our script.

– I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking “Yeah, OK Tim, this is called devised theatre.” Well no. No. Not reeeeeeeaallly. In as much as all theatre is collaborative, maybe. But there’s going to be a script, you see. I’m writing a script. Like, a proper script. It’ll have page numbers on it and everything. It might even have the words “THE END” written somewhere near the end. And once we’ve got it we’ll treat it like any other script is treated in a theatre. To my mind that makes it just like any other piece of new writing.

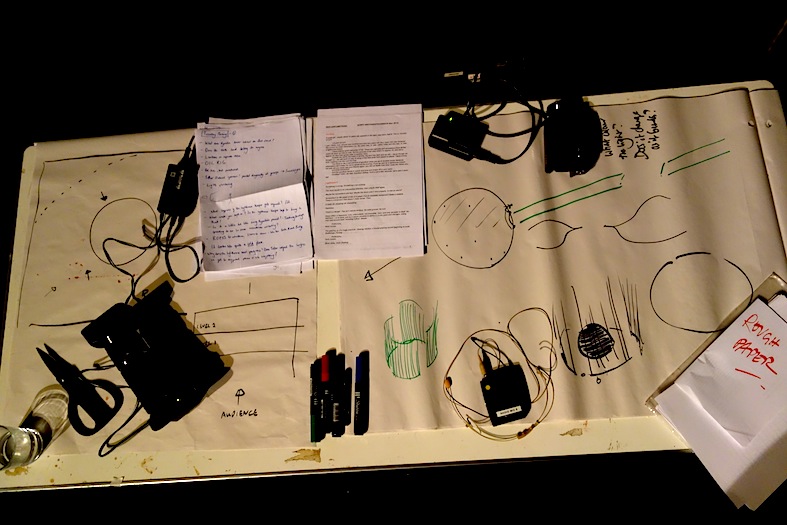

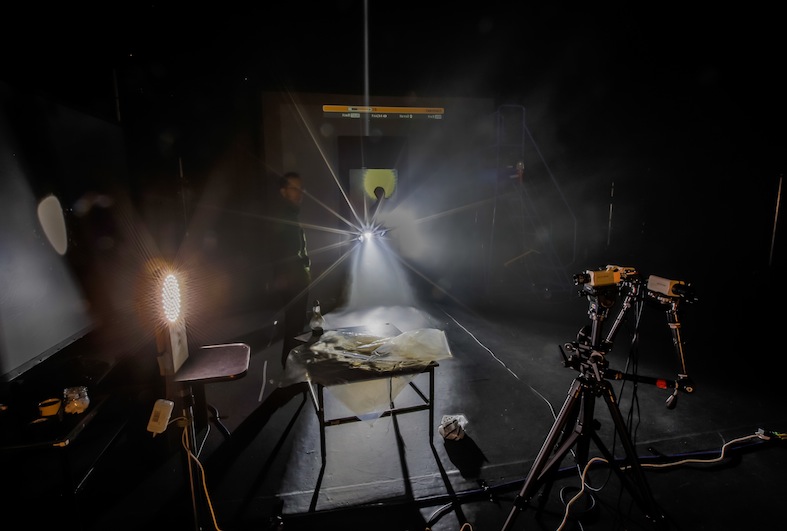

– Back in June this year we went into a week of R&D at the Wickham Theatre, Bristol. With a bunch of excellent collaborators, the aforementioned fragments of text and heap of equipment, we set about making space stations, routines, cataclysms and empty / not empty rooms. We used LEDs, projectors, hazers, plastic sheeting, mirrors, raised platforms, discrete loudspeakers and microphones and gauze. We played Ben Frost and North Sea Navigator and Dusty Springfield and the sounds of glaciers, wire fences in the Australian outback, a gospel choir from Baltimore. We amplified the fizzing whine the parcans made and cranked it until it sounded like the whole room was about to fuse. We asked production manager Chris Swain if we could rig massive lights in unlikely places. Our actor Jessica Macdonald moved in and amongst all this, and sometimes floated in space, and sometimes railed and ranted at the dark, and sometimes didn’t say anything and instead just stared into the void, transfixed. All this time Tanuja and I were asking not so much “what does it look like?” but “what does it suggest?” Because this week of R&D had several questions, and the main one I had to focus on as writer was: how does it feel?

– One of the big questions of content we had for DLLH is: what does our lighthouse keeper do all day? What are the tasks, where are the lulls, how much routine can we show? Just from watching Jessica struggle with a practical light in the darkness, I began to imagine a world where the standard universal physics seemed if not broken, then at least sluggish. A place where light has to be kicked around, jump-started, sculpted and coaxed. Our lighting designer Ben Pacey removed the lens from a fresnel lamp and Jessica, wearing welding goggles, held it into an upward channel of light, making an aurora over our heads. Sometimes just watching people do stuff with care is intriguing, sexy (I often think this is why I enjoy companies like Elevator Repair Service – because they tend to have people doing things, rather than just saying or representing things) and the R&D week has given me a kind of base language for daily life in the lighthouse: an idea of how physical our lead character’s routine is going to be. Halfway through the week Jessica turned to the group and said “You know, I’m wondering if [lead character] Teller speaks at all, ever.” And I thought: yes, that’s exactly why we’re doing this. To plant that kind of seed.

– We were trying to make a ghost, and our projectionist Rod Maclachlan gave the projected image a compression, a pixilation – nothing drastic, just something like CCTV blown up life-size. The ghost, already glacially slow, its aspect statuesque, developed an on/off shimmer at the edges and when it moved its arm in a greeting from the grave, its limb shifted in blocks, a distant memory moving byte by byte. And I thought of the economy you’d need in an interplanetary culture. How a universe bound by the speed of light would have to communicate, probably very simply: how planetary colonies might let each other know of their continued survival by setting off huge luminous explosions in deep space, beacons, smoke signals. Fireworks to say “we’re still here, we’re not done yet.” Safer, more effective than radio emissions. And how little you could carry with you on a spacecraft – how even digital data could be terribly bulky. You’d think that a future technology might look pristine, near-perfect to us. But there’s an argument that it might, conversely, have to downgrade, back to basics. The pixels might have to be recycled. And I imagined the pictures Teller might carry with her onto the lighthouse: perhaps her family (long since departed, thanks to the inequities of near-light-speed travel) captured in digital form, but reduced to a bitrate that made their eyes one pixel apiece and their features a defocused haze. And what would happen if one night, as Teller was looking at that picture, those digital blocks started, very slightly, to move?

– So, yes. This is how I’m writing Dark Land Light House.