Over the next few months I’m about to start working as a dramaturg and writer alongside some great artists, as well as giving a few talks and workshops about sound design for performance. When describing my methods I sometimes use phrases that are shortcuts to wider thinking, to ideas I’ve developed or adopted over the years about why people make art. And often, these shortcuts are only really meaningful to me… unless I ramble on interminably to clarify things.

So I thought I’d combine these ideas into a bit of a rant about theatre, writing, politics and creative process. In laying them out I began to realise how much of a problem I have with how drama is developed for the stage in the UK, particularly new writing. The methods often strike me as moribund, surprisingly subservient to conservative political and economic thought; and at the moment I think new writing is not really doing one of the most important things art can do – imagine other worlds, other ways of being.

How people tell different stories on stage

Three things on my mind of late (yep, I only have room for the three, it’s not the world’s biggest hotel) are…

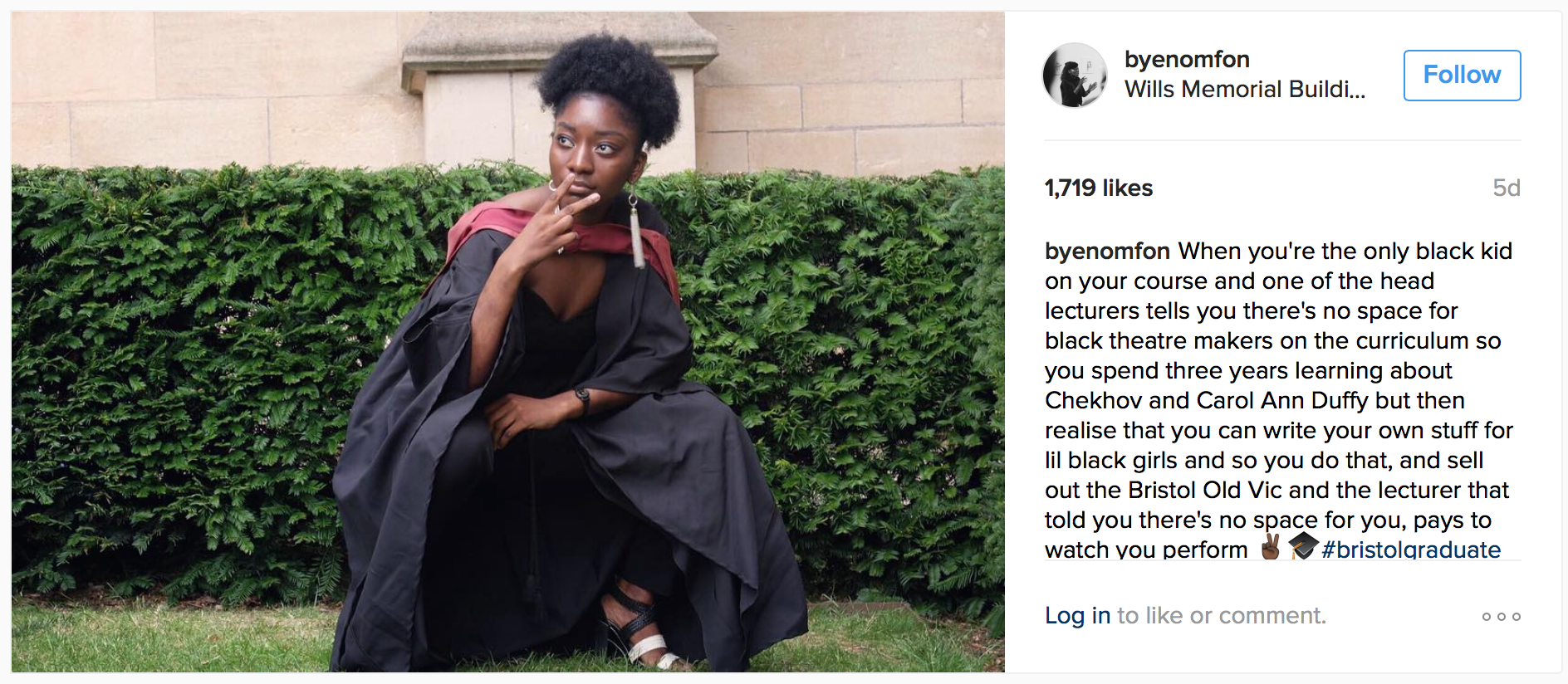

Eno Mfon’s story, here:

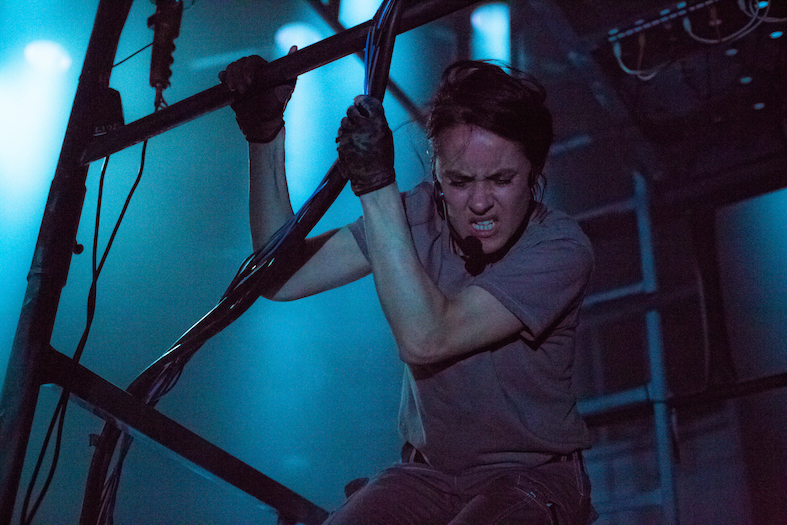

And, in the same theatre where Eno will have worked as a student, I saw a production by Splint Theatre, formed from Bristol Old Vic’s annual Made In Bristol scheme. A young company, a scripted production from devised material.

I loved Eno’s show, Check The Label, and I loved Splint’s, Out Of Sky. They were both funny, poetic in a ramshackle way, full of different voices, in love with language and music. Their modes of performance – unforced, responsive, an infusion of different tones and influences – were like a breath of fresh air when most of the stage plays I’d seen around them had been tempered, muted even, by tradition or aesthetic.

And I wondered after each show what the creators’ journeys would be like from this point onward. I wondered at their resilience so far, and what they might soon face. I felt slightly sad at the idea they could end up on some development programme that, with every good intention, might recommend they begin making increasing, accumulative ‘sense’ of what they created.

Because I’m starting to believe that this drive to ‘sense’ and absolute clarity of purpose in arts education and development is unhelpful, and maybe even dangerous.

Which brings me to the third thing on my mind: the world. Yeah OK. Bear with me.

1) Our current global culture is one where fascism of various stripes is on the rise. The protagonists at the moment are your standard appalling comedy fascists – but these comedy fascists, when they achieve any degree of power, just turn into straight-up fascists, ‘us versus them’. We know this. But their supporters are very often ordinary, often scared, often hopeful people.

2) Also, our world is one of increasing self-awareness and self-definition, of manifest rights, of technological empowerment. A mess of voices, complex and contradictory, it demands more and more of our time and energy. To the uninitiated it feels like a minefield of interests and concerns. But its adherents are often ordinary, often scared, often hopeful people.

Now I’m going to tell you that

1) applies to Wikileaks.

2) to Brexiteers.

Now I’m going to tell you that, no, no –

1) actually applies to Donald Trump. Obvs.

2) to the fight against race, gender and social prejudice. Obvs.

No, wait…

1) applies to Jeremy Corbyn.

2) to Jeremy Corbyn’s supporters.

Or –

1) to mainstream media moguls.

2) to free markets and global finance.

Etc.

This isn’t just an ‘oooh I got you’ exercise in relativism… (I hope.) It’s about the techniques used to set pretty much anything in opposition to anything else. About playing to assumptions, and how easy that can be.

Using drama to sell any old story

In most of my working practice I deal in dramatic form, in some way. In radio, TV, film, stage and prose the principle vehicle for my work is usually drama – much as I love non-narrative art. Even my music tends towards cinematic atmospheres, my song lyrics towards definable characters. So bluntly put: yes, I love drama. On screen I especially love genre drama, good versus evil.

Question. Could this wonderful form, loved by so many human beings – one that enables us to tell stories bigger than ourselves, to imagine other lives – be contributing right now to a more harmful way of looking at the world? A way of seeing the world that deals in binaries, in ‘us versus them’?

I think about some of the maxims that apply to writing drama:

Drama is conflict.

Make the conflict clear.

What do your protagonists want?

Show it. Make it part of who they are.

What are the obstacles to their goals?

Make them big. And numerous.

How bad can things get for your protagonist?

Make it worse.

Then I think about how the news is reported in the modern age, and the techniques are exactly the same. The way the ‘facts’ are presented, it’s basically: DRAMA. News outlets compete for audiences, and to get bigger audiences they make the news into easily digestible dramatic narratives. Unstoppable forces, immovable objects. It’s not just the requirements of balance in journalism that lead to climate change deniers having the same airtime as the 99.9% of scientists who have studied and charted man-made climate change in unflinching detail: it’s the lure of drama. The director David Fincher said for an argument between characters to be truly effective, the writer needs to make every character, somehow, right. But in the real world it ain’t always so.

Back to Eno Mfon and Splint Theatre. Their shows never quite led the audience anywhere definitive, never quite posed definitive questions, were not merely a soap box for their makers. They had their own distinct voices, but were refreshingly unobsessed with them.

Thanks to some insider knowledge on both productions I know these abstractions were often a worry for the artists, a concern that their intentions or storytelling might not have been clear. By the time I saw the shows, those issues had either been resolved, or as an audience member, I didn’t mind that I was left alone with them to draw my own conclusions. It felt like being alive, as opposed to being sold something.

In one section of Eno’s show she, a dark-skinned black woman, danced with abandon to a collection of music videos that fetishised pale-skinned black women. This moment went on for ages without any other comment. Eno might have lost energy towards the end. The audience too, perhaps. But that was the point for me: the cavalcade of images, Eno dancing to the different rhythms, the accumulation of absurdities, problems and joys. It was amazing.

A contrast. The critical dialogue around a recent production of King Lear at Bristol Old Vic. In almost every review, critics went out of their way to speak of Brexit… and therefore the ‘timely’ nature of the production.

Fuck me. Barely a single write-up that didn’t connect Shakespeare’s apocalyptic, surreal, stompingly pagan, rage-filled story of deep philosophical complexity and existential woe, written in the 17th fucking century, to an issue-of-the-hour, as if it were a David Hare play. Sure, you’re welcome to attach Brexit to Lear if it really floats your boat, but it’s an accident of timing, nothing more. That’s the thing with Shakespeare – old beardy was such a populist he wrote about everything he could, and eventually you can connect pretty much anything to his words.

But this critical blanket response was symptomatic of something deeper. Because this is how we’ve become conditioned in UK theatre, perhaps elsewhere too: expecting our theatre-makers are saying something to be understood, to be accepted, to be regarded as important or relevant if ‘successful’. It’s a codification that locks out other, wider audiences, those interested in different results, the many other kinds of storytelling the world has to offer. As Stella Duffy has put it, our artists are being conditioned to be ‘great’, consumers to expect ‘greatness’.

Drama and certainty, drama and clarity

Yes, you want people to enjoy the journey they’re on. But do you always have to point out exactly what they should be looking at along the way?

My take is: drama that holds clarity of statement paramount becomes little different to the current use of drama in reportage. The language, the feeling of the art, matches the mainstream discourse about culture, politics and economics. It presents clear established factions, acceptable middle grounds, simplistic binaries. As a result, a piece of theatre that claims to ‘ask questions’ is usually simply acknowledging something at length. Whole audiences spend their evenings just nodding at poverty or racism or cyber-bullying or worldwide financial collapse – because the sheer fucking complexity and knotiness of these things has been ironed out by the need for the author to be clear.

A contrast: David Hare’s Via Dolorosa. A luminous thing, a solo performance for the playwright, where he walks the disputed territories of Palestine and Israel, and recounts the words of those he meets. On stage, he raises his hand to indicate that a voice other than his own is speaking – a haunting ritualistic gesture. He relates how parties on both sides repeat variations upon ‘they just want to kill us all, it’s as simple as that.’ Vivid and heartbreaking; a performance by David Hare himself that feels like the least David Hare thing he’s ever done.

I guess in some ways it’s a question of what we want from our art, and there are many things an artist can give. But the growing creep towards playwrights, especially, being creatures of certainty and conviction, making work that sits comfortably in their own world, strikes me as a patriarchal and commercial model. It’s only one possible model.

Artists as leaders, as ‘relevant’ or ‘important’. Why?

I’ve recently been reading Alastair Campbell’s complete published diaries. They give a wonderful, vivid, drily funny account of his time as director of communications and strategy at 10 Downing Street, and an even better account of a political environment in which absolute unflinching certainty became the only possible game in town. Campbell and his team seem to spend a great deal of time engaged in semantics and repetition, framing the established government line over and over for a wild variety of different contexts, all the time wrangling with a media that demands novelty and drama. Tony Blair’s method of formulating these lines is to have the same conversations again and again with Campbell and others, a one-man groundhog day, attacking the issue from every possible angle to ensure absolute clarity.

It’s understandable how this culture prevailed. But complete unflinching certainty isn’t really a common phenomenon in everyday life. I can’t help but feel that somehow, contrary to received wisdom, it contributes to keeping politicians distant from those they need to reach. Blair was the epitome of a conviction politician, he spent a huge amount of time saying precisely what he thought – yet people barely remember what he truly stood for.

I go to lots of plays and emerge feeling exactly the same.

What interests me about working on the stage, in live performance, is that it’s one of the few places left for fictions that feel truly vulnerable, where ‘not knowing’ is OK. And what’s more, the audience will accept that vulnerability in a theatre. Maybe it’s because when we’re gathered together in a room, that’s already a story we’re all part of, before any fiction has even begun.

The choreographer Joke Laureyns says it far better than I can, on the subject of making theatre for young people:

“There is, in my experience with young audiences, always a degree of wonder about what they’ve just witnessed. Mostly, it is a boundless not-knowing, now-knowing how to process what they have seen into language, or to name the kind of viewing experience they have gone through. And that is a good thing: I don’t think that art for children should meet their expectations, I think we can serve them much better by showing them something unfamiliar, something which will raise questions and put the world in a different perspective … offering some breathing space between all the certainties they are brought up with. It gets better even, when the grown-ups do not seem to know the answers … when there is the beauty of doubt, opening doors to philosophy and to mental wealth.”¹

Brittle, barely tenable narratives – ones that feel as though they might collapse at any minute – are not really viable for TV, or feature films with anything approaching a large-scale budget. In the UK the costs of producing TV drama, and the scarcity of opportunity, preclude taking extreme risks with your subject matter. The sheer scale of collaboration involved makes selling and producing narratives a constant demonstration of confidence, and this confidence usually transfers onto the screen in some way – meaning the language of most TV drama is sure-footed, even when portraying chaos and confusion. It has to be, given that the audience can switch off at any second… although gratifyingly, there is audience demand for a certain standard of material in this country thanks to the influence of the BBC over several generations. The price you pay is a general veering away from nebulous, holistic ideas that are truly difficult to handle. I reckon the one place you’ll find truly vulnerable narrative constructions on screen is in progressive documentaries made by film-makers outside the news mainstream – stories that feel able to say: “I don’t know. We don’t know. Nobody really knows.”

I’m always a little suspicious of claims for the benefits of a given artform over any others. But I do believe I see some of the most truly open and flexible dramatic narratives in live performance; in events where artists and audience are gathered in a room together, where we’re all complicit. It’s here that I experience stories that, in Tom Waits’ words, have “a leg missing” and actively need the audience to help prop them up. It’s a quality I frequently detect in live art, concerts, performance lectures, dance, circus, installation and interactive art, street art and sound walks, gigs, DJ sets and devised work. But recently I’ve found it less and less in scripted theatre.

Is it because the dominant methods of dealing with scripted narrative come from those textbooks and style guides produced for screen? Is there an infection of McKee, Mamet, inciting incident, character arc etc, in playwrights’ development – all valid workable guidelines for Hollywood, but predicated towards a very specific system of distribution? How much do those big macho screen rules have to do with the stage?

Audience, space, time

Some brilliant theatre:

Portraits in Motion, Volker Gerling, Mayfest, Bristol.

Gerling tells us stories of people he met travelling on foot through Germany, taking rapid sequences of photographs that were then turned into flipbooks. He projects the flipbooks onto a large screen, first image resting on the top, static, while he recounts meeting the portrait’s subject and what he learned of their lives. Then he deploys the flickbook, three times. As the pictures ripple and move there’s simultaneous ripple of noise and movement through the audience – sometimes sad, sometimes jubilant, sometimes perturbed, sometimes in collusion, sometimes in judgement. But always complicated. These ripples are always hard to properly measure, and it’s where the true magic of the show lives.

Live set, ANOHNI, Sonar, Barcelona.

The audience are waiting for ANOHNI to premiere her live show in the late hours of Friday night, but she doesn’t take to the stage for 15 minutes. Instead there’s a film of Naomi Campbell dancing in slow motion, the camera dollying back and forth, a rumbling, fizzing bass drone slowly building, louder, louder. The audience shift on their feet, look around: what? Why this? Eventually the sound dominates, the chatter dies away. When ANOHNI finally appears she’s cowled, veiled, and will remain so throughout the gig. With each track, a different woman’s face appears, huge on the screen behind the singer, lip-synching the song, properly iconic in the old sense of the word: their eyes are windows. ANOHNI flings herself around to the music, lyrics about global warming, sexual abuse, drone bombs, modern disconnection, love.

Nelken, Tanztheater Wuppertal, Edinburgh International Festival.

A lone, willowy man in evening dress walks to the middle of a stage covered in a low blanket of multi-coloured carnations. Sophie Tucker’s version of The Man I Love plays through the PA and he performs a mannered, precise and ornate sign language to the lyrics, all the time looking dead ahead, blank. When I see it in Edinburgh in 1995 this moment is greeted with a kind of delighted, hushed awe. Many years later, when I see a YouTube of a different performance of that same moment in the show, for some reason parts of the audience are laughing their heads off.

All these moments above could form part of a scripted drama. I’m convinced of it. I don’t see what, in theory, could preclude that. They’re acts of imagination and magic.

Except – they’re about the audience as much as the content.

A question often asked in playwright development workshops is: “so, what do you need to write a play?” I’ve heard the question posed in such sessions three times, and no-one ever replied: “An audience.”

And yes, maybe it’s a semantic, pedantic trip-up, maybe I’m being a complete wanker. Do you need an audience to write a play? It’s a holistic point, but I reckon it’s essential. Without holding in your head the potential performance, including the live audience, your script is just a specialised form of prose. I think this might be part of the malaise. Plays as literary endeavour, plays designed to work on the page. Plays written for the logic of a reader – not for the messiness of a theatre where the mood of the room can, and will, change everything. Four-star review plays. Nodding plays. “I see what they did there” plays.

My own journey through writing development has been a charmed one, and I’ve worked with some truly excellent people. Because I’ve come late to writing as a career, spending quite a few years swerving from one artform to another, I was able to begin by producing my own work with my own company, about seven years ago. That was the catalyst for pretty much everything that followed. The feedback I’ve received on my scripts has been generally excellent – intelligent, helpful, non-dogmatic.

But full disclosure, given what I’m banging on about here: I’m really not sure my work translates well to the page. I’m still pondering over how to transpose the different kinds of chemistry I experience in an audience into the form of play texts. So I leave a great deal of space in my scripts, for discovery in production. Characters’ intentions are sometimes opaque, stories are sometimes derailed or reversed, narratives are not necessarily the driving engine. And as a result I suspect a lot of impartial readers look upon my unproduced plays as incomplete, not fully versed in the craft of scriptwriting. I fear the reader who asks how a play reads, what sense it makes, not how it might feel. The reader who assesses plays on a points-based system. The reader who makes a category error, assuming I’m writing a play to be nodded at.

Tick boxes, compartments, shelves, price tags, star ratings, easy gradations of value and worth.

Quality plays with

clear authorial intent and

well-trained actors, lit

so that you can see their faces

AT ALL TIMES

speaking

CLEARLY enough

to hear

every

word.

How writing clear, easy drama can become politically subservient

Radically simplifying something to make it sellable is obviously a valid creative choice, but it obviously filters the content. Be it a film, a play, or a news story, a politician – after a while the reductio ad absurdam can kill you. The current state of the Labour party is a great example. It’s not just being packaged as a drama. It’s a really, really BAD drama.

The delineations between factions, the broad motivations, the facile binaries – it’s a trite movie, full of people over-exaggerating stuff. You’d skip over it on Netflix without a second thought. Depending on which side of the divide you fall, Jeremy Corbyn is portrayed either as some kind of Ghandi, or an Islington Chairman Mao – when actually I suspect he’s more likely to resemble Bunny Colvin in The Wire. [WARNING: skip to the end of this paragraph if you’re avoiding spoilers for The Wire.] Because it’s complicated. Bunny Colvin is principled, he’s often right, and he’s completely doomed. We love the fact that he’s standing up for honesty and social justice, it feels positive. But the context is wrong. The imbalances, especially the professional ones, just haven’t been thought through. They’re the tactics of a man who after many years, thinks he has little to lose.

The Corbyn conundrum is obviously similar to the Trump travesty, on the most basic of levels: two iconoclasts with idealistic policies, but on opposing sides of the security / social justice axis. Both deliver impressive-sounding promises, both seem reluctant or unable to show their workings. But this phenomenon doesn’t feel new to me, in fact it feels very very old indeed. It feels like a supreme rupture of some familiar tropes from the last few decades. It’s about promises you can’t keep.

There’s something about the 20th century, with its rash of mass media advertising, its near-pathological aspiration complex and its superstar politicians, that makes me think of it as the age of promises. And not just in politics and economics… the ‘promise’ has formed the principle contract between artist and audience for much of that time, too. The artist promises you something, and then you judge whether the artist has delivered on thrills or laughs, or sheer euphoric highs, or the number, and depth, of deep thoughts provided. But that was the 20th century, and it’s gone. I think anyone who wants to make interesting forward-thinking art now operates not in terms of promises, but invitations – the potential for the audience to be part of something. Being ‘part of’ doesn’t necessarily mean interactive (although it does mean interactivity is a formidable tool) but rather it’s about an attitude in how a story is conceived and deployed. It’s how art is currently offering up a different way of looking at the world, and inviting its audiences to be complicit in the dream.

A few examples:

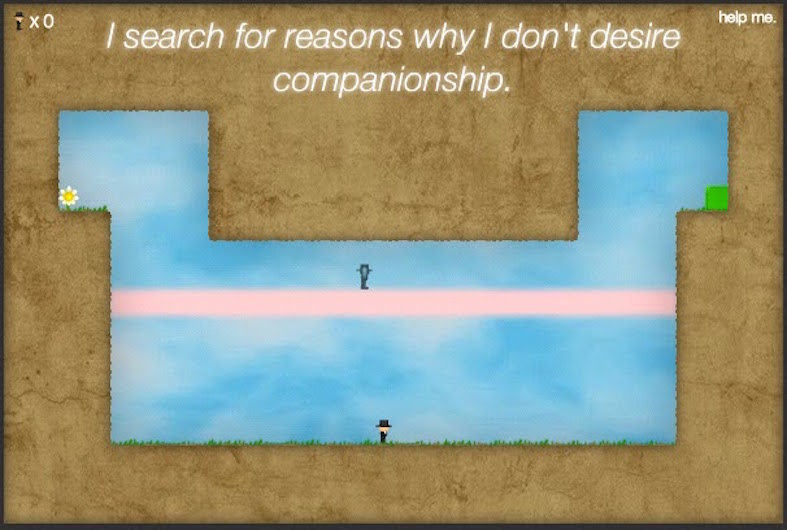

– in gaming that is as much about empathy, meditation and sharing as it is about competition and cathartic violence. One of my favourite online games is called The Company Of Myself by Eli Piilonen (bear with the link, wait for the ad to vanish.) In its accumulating puzzles, it somehow ends up being about loneliness and co-operation at the same time – and for something so graphically simple, hits you with some surprising emotional punches.

– in the work of theatre companies like Elevator Repair Service. ERS often adapt non-dramatic texts for the stage, and Gatz, their 7-hour reading of The Great Gatsby, is perhaps the most astonishing piece of theatre I’ve ever seen. On a stage dressed to resemble a random American office, down to the smallest detail, a cast of downbeat workers slowly become the protagonists of F Scott Fitzgerald’s novel. They burst into louche dialogue while filing paperwork, or emerge from a typing pool to dance on a table. It inhabits a space somewhere between reading, representation and re-enactment, and has no truck with mimesis, that frustrating obsession British theatre just can’t seem to get over: Gatsby himself is a balding, bored boss; Jordan Baker, lithe and bohemian in the novel, is played by a dark mercurial sprite of an actor. After a while the contrasts not only don’t matter, they also add further complications and joys to the story. The invitation of Gatz is so simple, so brilliant, it’s just: ‘stick with it.’ Scott Shepherd’s narrator is – like the best pop vocalists – completely unselfish and unshowy in his delivery, measured and clear, allowing the text to breathe for performers and audience alike. Some critics are perplexed by ERS’ style. I’ve heard audience members say “it’s just not acting, is it?” Well, yes it is. Just the best possible kind of acting for the luminous uncertainties, secrets and self-denials the performers are representing.

– in the sneaky triumphs of fan fiction. One of the most joyous examples of mass collaborative storytelling is Doctor Who, arguably the first instance of a fanbase successfully reviving a long-form TV series they grew up with. The happy geeks who dreamed up spin-off novels or audio dramas during Doctor Who’s off-air years are now the new series’ official writers, and they keep plenty of space within their stories for future ones dreamt up by new fans. In a DVD commentary for one of his final episodes as showrunner, following a list of intriguing names and incidents mentioned rapidly by the Doctor without any further explanation, Russell T Davies addresses the listener and says: I’ve no idea what any of those things are. Those names are yours now. Do with them as you will.

– in responses to the way new technologies demand a different financial model for the making of art; especially, at the moment, in music. The connect between musician and mass audience is potentially so much closer than it ever was; sometimes almost symbiotic, but febrile and problematic too. People are paying less and less for their music. When they do, more and more of them are choosing routes with minimal mediation, different to the corporate model of audience > record label > artist that dominated 20th century music-making. Artists running a ‘pay what you like’ or ‘minimum payment‘ option are discovering that it often brings in more money than a defined price. This is a particularly interesting issue for me as the fluidity and complexity of ‘who owns the music?’ makes it very difficult to form a cogent moral argument. I believe artists need to earn a living from their work – but I don’t believe mechanised, formulaic distribution of the kind represented by large record labels is a healthy way of discovering or experiencing sounds. For anyone wanting to make a living in music it’s a dangerous time – but in terms of what that music might be, and who could make it, we’re living in the most exciting times yet.

So… in this theory (thanks for bearing with me) the shift towards ‘invitations’ is responding to a culture that has focussed for too long upon self-interest, greed and appropriation, the hoarding of wealth as the only reliable means to achieve all other aspirations in life. In contrast, work where the playwrights’ voice is everything, preaching to the converted, ends up feeling like part of the status quo. If your play is effectively a cogent argument, with clean-spoken characters whose dialogue is permanently useful to the plot, what room are you leaving for an audience to dream with you – unless you’re making a huge social assumption about that audience? Are you just writing for the theatre-goers that already exist?

The amazing world of unnameable thingsTM

Art has always had the ability to dream up different ways of living, so it would be hardly surprising if in recent years progressive artists were thinking more about sharing, about community, and interactions of many different shades (in the way that Harry Josephine Giles talks about how we care for audiences in their excellent essay, for instance.) Artists are drawn to make works that invite people to imagine more, to imagine better – and to include more people in that act.

Are these modern ambitions particularly visible in mainstream UK theatre at the moment? Much as I love it, for me, most of it is not really modern in any recognisable way.

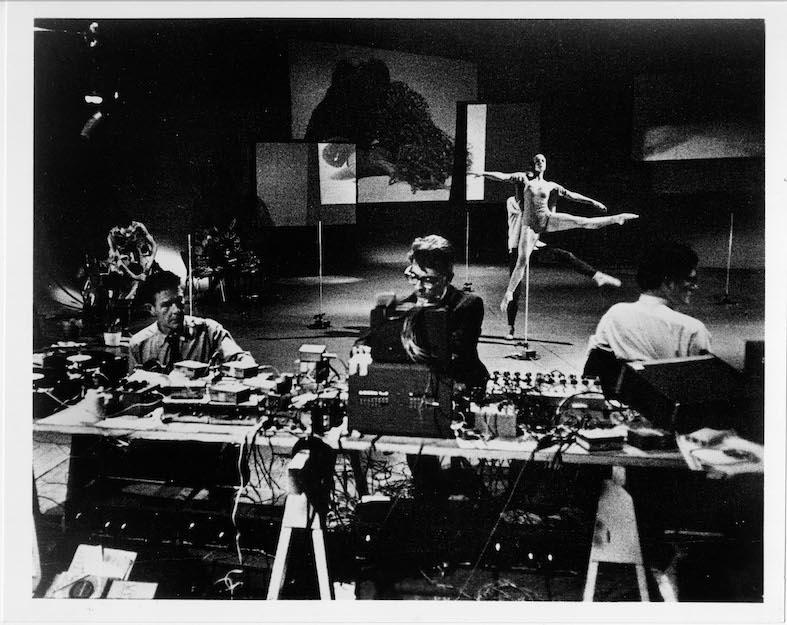

Granted, theatre is often wonderful precisely because of its ephemeral, fleeting nature. Sometimes it’s truly inspiring to be working in an artform that doesn’t really have a memory. But I also can’t think of many disciplines where you can be lauded as innovative or experimental for doing something that was first practiced 60+ years ago. Did theatre have a ‘punk’ moment? Maybe, at various points, with playwrights like Orton or Bond or Kane. But did it have a post-punk moment, when that creative vigour was translated into aesthetics that informed pretty much everything that followed? I struggle to think of a comparison. Subject matter, contemporary references or LED lighting aside, most mainstream theatre in the 21st century could very easily have been made in the 1960s.

This isn’t an argument for the annihilation of any particular kind of production. I work on, and love, dramas that revel in conversation, unfolding exposition, careful stagecraft. And I know that there are plenty of clichés that manifest themselves in every aspect of performance-making, no matter how progressive (a good friend, also an avid theatre-goer, has started to get particularly tired of a type of show she describes as “Solo Hipsters Talk About Their Lives.”) But I look at the multifaceted nature of modern music, I hear the fractured, complicated, almost infinite ways in which any song can be written and experienced, and I’ve gotta ask: how come I’m only seeing 3 or 4 different ways of writing a play? No matter what qualities you think separates the artforms, that ratio isn’t even funny.

Somewhere, deep in the marrow of theatrical practice, there’s the call and response of the oldest kind of human storytelling. There’s the being-together, the making-it-up-as-we-go-along, the this-isn’t-real-but-tonight-it-is-real. I’m convinced that audiences alive to the magic of performance can not only handle some uncertainty and danger – they desire it. I don’t know if theatre can continue to be properly relevant or interesting to new audiences if it continues to promise like a party political broadcast, over-dramatise like Fox News, and dance like your dad.

In her amazing book Dancing In The Streets: A History Of Collective Joy, Barbara Ehrenreich charts the mixed fortunes throughout human history of ecstatic collective actions; those essential events that evoke a connection to something bigger than oneself, through ritual, noise and movement. Reading her accounts of the rise and suppression of carnival, of the surge in modern melancholy alongside the loss of ecstatic rites, of murderous colonial crimes against native cultures, of the racist scorn thrown at rock’n’roll, I was left in awe of how many of humankind’s most binding, catalytic stories are communicated in powerful, visceral experiences we can’t adequately describe using language.

And then it struck me how so few of my favourite or formative theatrical experiences have been verbal, intellectual ones. So my memory of the first time I saw Krapp’s Last Tape returns to me in images of David Warrilow fumbling with bananas and spools, the hang of his face as he listened to his past self – the text of that play is a different thing entirely, it would shift and re-set with each subsequent production I saw.

Elsewhere… I remember Simon McBurney’s spittle-flecked downstage rage in A Winter’s Tale… or Liz Aggiss balancing precariously dead centre of a completely bare space, singing a song about set theory in German during Absurditties… or the slap of the performer’s sweaty bodies hitting the floor and dragging themselves down the length of the Wickham Theatre in Goat Island’s We Got A Date… the sheer dream-like filmic fug of Lippy by Dead Centre… the protagonists emerging from a dense crowd of Broadmead shoppers at the start of Back To Back’s Small Metal Objects, audible on our headphones long before they were visible… and Eno Mfon dancing to idealised images of pliant, pale-skinned girls. All moments when it felt completely electric to be in a place, with other people, feeling something. Feeling, not necessarily understanding.

How people make different things

There’s an element of personal taste to my problems with new writing, but I know I’m not the only one tired of plays where performers are just walking mouthpieces for the author. Plays with three actors, a clearly-defined issue, and an act of violence at the end. Plays where people stand around telling each other what’s happening. Plays which feel like they’re from exactly the same universe as other very similar plays, but it isn’t recognisably the universe we’re currently living in – a strange, mannered parallel dimension where people shout their feelings and move their forearms a lot.

I can’t claim to know what the best way out is, towards something more exciting, less predictable. I suspect it’s knotty and complicated. I haven’t spent long enough within any organisation to suggest elegant solutions in a sufficiently informed way. In the spirit of earlier comments I feel compelled to say… I just don’t know for sure.

But the most important tactic seems essential to me, whatever its ultimate aims: get different people, from different backgrounds, interested in writing for theatre. And not, crucially, the theatre that already exists, but the theatre they would like to see. This probably means venues blurring the lines between outreach and literary departments, seeking out talent before nascent writers have formed a restricting idea of theatrical practice.

Because writers who already identify as playwrights will be well versed in what venues appear to value and promote, right up to the conditions of submission on the website (“No musicals” it might say, discouraging any writer with a heritage where narrative is synonymous with song.) And I suspect that readers need to come from different places too. If, as is often said, developers want plays that in some way speak of ‘how we live now’ – who is making that judgement, what’s their baseline? What strategies are there for introducing our dramaturgs, readers and editors to more of human experience, to morals and values beyond their own? And if we don’t think that’s the job of a theatre… then what are theatres for?

The established, well-worn hierarchy of production process in a lot of venues doesn’t always help the situation. The act of sharing often gets pushed to one side through fear of treading on someone’s toes. I don’t know, for instance, how often I’ve seen a writer in a rehearsal room that’s not for one of their own plays, with all the no-strings education that could provide. I don’t know how often group writing is advocated as a desirable skill in the theatre world, when it’s perhaps one of the most valuable dramaturgical tools you can ever develop, whether you’re an accomplished solo writer or not. And I know from personal experience, as part of some truly excellent writer development schemes, that there’s no better eye-opener than negotiating your way through a story with other writers, with different lives and viewpoints.

Because in the end it’s not just about understanding what we write. It’s about asking why we’re writing it in a particular way, what it’s for.

It’s when someone says: “I just don’t think the audience will get it,” asking: “what audience, exactly?” It’s not letting that assumption pass until you’re satisfied it’s not a prejudice or a statement about comfort, institutional or otherwise.

It’s never, ever saying “…but it’s not theatre.” Especially when maybe you mean, “it’s not drama,” or “it’s not how I understand theatre,” or “it’s not for this theatre.”

A final contrast. I love an old-fashioned, well-made play when it’s done well. You might not think it from my screed so far, but I really do. Sure, the last example I can think of was from a year ago, a modest production by Theatre West of Trip The Light Fantastic by Miriam Battye; subtly drawn, deftly performed, quietly stretching your heartstrings. But in no way do I yearn for the death of the kind of experience traditional audiences know and love. I’d be a screaming blue hypocrite of the highest order if I were to deny the people who adore nothing better than a couple of hours of Alan Ayckbourn, an interval drink, theatre as a comfortable social function, or as a subconscious marker of how measured and introspective our middle-class lives can be… I do exactly the same thing every time I slump on the sofa and watch a full series of 24 in one day. To my mind one of the most beautiful audiences I’ve known is at Oran Mor in Glasgow for the A Play, A Pie, A Pint seasons; a crowd that skews senior in the early part of the week before tumbling into something more demographically diverse at the weekend, consistently faithful, and completely in love with seeing plays of wildly different stripes from one week to another, talking or arguing about them in the company of food and friends.

This is no argument to abolish anything so lovely – it’s just a suggestion that all of this could be even more vibrant, even more diverse, even more vital. There’s room for so much more. Audiences in the 1960s would barely bat an eyelid at what we’re watching right now; bad language and technology aside, it would be theatre pretty much as they understood it. The theatre of tomorrow could have byroads and vistas, transports and participants the likes of which we, its audiences and makers in 2016, can only dream of. But guess what, duh: we can dream. That’s the whole point.

¹ extract from ‘Some Thoughts On Dance For Young Audiences’ published in One Step Beyond: Interdisciplinary Exchange, the annual magazine of ASSITEJ 2016.